D-handled Rivet Buster. Pinch hazard.

A reminder to members working with “D” handled rivet busters. When you get working in tight quarters, it is too easy to get your hand pinched between a piece of steel and the handle. Be careful out there.

Teck Coal Greenhills, 4 APPRENTICES NEEDED

2 day shift 2 night shift apprentices, confined space, fall protection, whims 201t5.

October 1, 12 to 14 shifts Contact Greg Hanneschlager, 587-990-1503 .

Pine River Update Oct 8, ’19

The health department is inspecting mice infestation at the camps.

Good afternoon,

Your complaint regarding mice at Hasler Camp 24 and Little Prairie Lodge was forwarded to me for follow-up. I will visit Little Prairie Lodge tomorrow and will also contact the operator of Camp 24 to arrange a re-inspection if necessary (the photos you’ve submitted may be sufficient).

I will contact you with my findings. If the worker experiencing a persistent cough hasn’t already, I would recommend they seek medical attention.

If you have any questions please feel free to contact me.

Thank you,

Ali Moore

Environmental Health Officer

Our member’s inspection has confirmed that Camp 20 in Chetwynd exceeds the Camp Regulation Standards. If at any time a camp falls below standard you can refuse to live in it. Contact the Union if you have any questions or concerns.

Ken Nash is now the contact for Clayburn Workforce. 780-913-7442 mobile.

Pine River Gas Plant Shutdown, Shifts expected to be 7-7 with foreperson crossover. Night shift is in Camp 20 in Chetwynd. Day shift is in Camp 24 near the plant. They are dry camps. Ken will confirm with the union and workforce asap if any changes to shifts.

Clayburn needs more workforce for CNRL, and Syncrude on the hydro (Conversion is pretty much handled). They need API certified members for QC.

Working in Alberta requires a Urine test.

Travel to CNRL is under TAP agreement with local 1AB and is $550 one way flat rate drive or fly. Travel to Syncrude is $285 on the way in and $285 on the way out if you don’t bail.

Pine River Job and Camp Update September 07, 2019

Pine River Gas Plant, Sukunka Natural Resources Inc (SNRI)

There are Two Camps

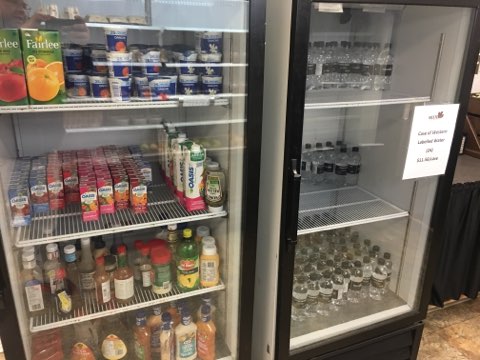

Flite Camp 20 is located in Chetwynd at 4414 44 Ave NE, Chetwynd, (250) 874-7445. This is the night shift camp. Night Shift will be bused in to the gas plant and returned to camp daily. This is a 166 person camp.

Flite Hasler Camp 24 is located at KM 21 Westcoast Road Chetwynd, approximately ½ KM from Pine River Gas Plant. This camp is for day shift. You are provided with secure vehicle parking in Chetwynd and bussed in to the camp. Clayburn will provide a van for on demand transport to Chetwynd during off shift hours. This is a 200 person camp. One bunkhouse is women only.

Both Camps are Dry Camps.

___________________________________________________________

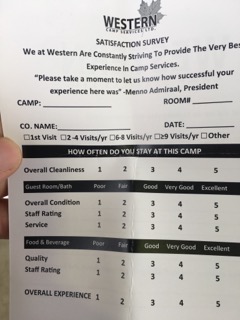

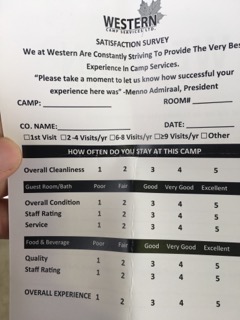

Inspections

Flite Camp 20 was inspected by a Clayburn manager on behalf of CLRA Friday September 6, 2019. It will be inspected by a BAC member Monday September 9, 2019 to confirm the contractor’s inspection. We don’t anticipate a problem. It appears comparable to Camp 24.

Flite Hasler Camp 24 was jointly inspected by CLRA and BAC August 26 2019 and exceeds our Camp Regulations.

Safety-Hasler Camp 24 Evacuation-SNRI Assures CLRA that the Camp is outside the evacuation zone of the plant and that this is a total shutdown, the camp is flat and there is not a gas release hazard. The plant has an evacuation plan. The Camp has a muster point and evacuation plan.

__________________________________________________________

The Job

Contractors-Clearstream is managing the shutdown. They hire sub trades but Clayburn Services is hired directly by SNRI (CNRL). Clearstream has what they call a union side, Clearwater and a non-union side Flint.

The job is 7-12 hour shifts per week for up to 23 days starting September 15th. Clayburn staff have not returned calls today to confirm any job/shift start times.

All of this as of September 9 at 9:28 PM. Any questions call or text the union cell phone. 778-847-2472.

Geoff Higginson

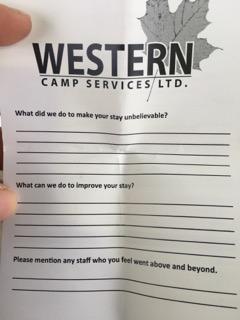

Hasler Camp 24 Photos

Camp 20 In Chetwynd

This camp is very similiar to Camp 24. More photos in detail on monday.

Urgent Need for 20 Bricklayers in Fort Mac.

20 bricklayers to Fort Mac. Clayburn needs bricklayers still…. Specifically we need our available Nozzlemen on deck. Contact the hall or Geoff Higginson as soon as possible. Even if you are working right now they could use you in a week or ten days. Let’s go…double bubble and full wages. The three bucks came back in the wage.

Letter to CLRA Contractors Re Double Time

Urgent Manpower Request for Alberta

URGENT-Request for Manpower

Alan Ramsay, BAC Local 1 AB (CNRL and Syncrude) needs bricklayers. Alan is soon to be in urgent need of approximately 50 members to properly man these shutdowns.

Contact our local union first and then Local 1 AB.

Horizon Day and Night Shift

Syncrude Days and Nights Hydro Nozzlemen

Geoff Higginson, President

International Union of Bricklayers & Allied Craftworkers

Local #2 British Columbia & Yukon Territory

778-847-2472 mobile, voice & text

Office:

IUBAC Local 2 BC

12309 Industrial Rd., Surrey, BC V3V 3S4

604-584-2021 telephone

604-584-2022 facsimile

1-855-584-2021 Toll Free

www.bac2bc.org

Correction re Thorpe Canada.

The union has been advised that Thorpe Canada has filled its workforce requirements for their upcoming jobs. If you are seeking work contact the hall or Alan Ramsay local 1 AB for the urgent call for bricklayers there.

Red Seal Completion

If you have completed your apprenticeship technical training and still need to write or re-write the red seal exam contact instructor Larry Heide through the office for information on red seal study information and consult with Sharon on how to schedule a re-write of the red seal.